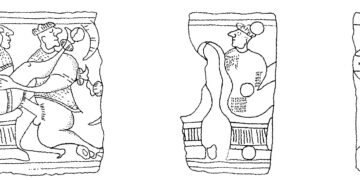

At the core of the concept, which was used in the last century to describe numerous two-handled ceramic vessels, are still Greek and Roman amphorae. They are pottery containers used for the non-local transport of agricultural products and their remains are scattered across all archaeological sites around the Mediterranean. Being the subject of intensive research, they provide to the archaeologist’s crucial information about the inter-regional and long-distance movements of agricultural products within the economic networks. Not only their shape, but also the production stamps on them provide us with information about their origins and the painted inscription, often displaying a millennia-old sense of humour, provide us direct information about their contents.

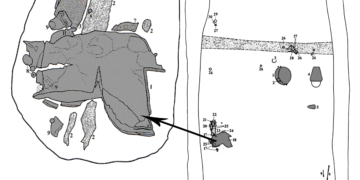

They were the first on a large scale to produce transport containers, artefacts that on a symbolic level even overshadowed their actual contents. Their systematic disposal created the first recognizable rubbish dumps in ancient cities – middens that rose to previously unprecedented scales such as the roman Monte Testaccio, consisting from assumed some 53 million amphorae. It seems that most of the amphorae were recycled, only the Iberian and north-African oil amphorae were too fatty to be reused and were systematically disposed of. The hill became a national myth in 1849 when Giuseppe Garibaldi positioned on its top a gun battery that under his command successfully defended Rome against an attacking French army.